Akwasi Frimpong can still remember the Christmas Day when a bottle of cola felt like a special treat.

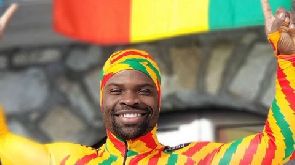

He also remembers living as an illegal immigrant in the Netherlands and the constant uncertainty of what the future held. Now he’s about to compete at the Winter Olympics and make history.

Growing up in a one-room home in Kumasi, Ghana’s second most populous city, Frimpong harboured dreams of becoming a professional sportsman… but he quickly had to accept his hopes might never be fulfilled.

Living with his grandmother and brother alongside eight other children, in a tiny room measuring just 4m sq, Akwasi went in search of a new life and, at the age of eight, followed his mother to the Netherlands, where he lived as an illegal immigrant.

Despite much adversity, including injury and the task of mastering three different sports along the way, Frimpong’s long-awaited dream finally became a reality on Thursday, when he will made history as Ghana’s first skeleton athlete at a Winter Olympics.

BBC Sport looks at the 32-year-old’s journey to in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

A challenging childhood

Akwasi and his brother were raised by grandmother Minka after their mother fled to the Netherlands in search of a better life for her boys. Their cramped home took its toll, however, and Akwasi fled to follow his mother… and his dreams.

Determined to settle into his new lifestyle and communicate with his peers, Akwasi borrowed books from the local library in a bid to learn Dutch.

But Akwasi was hiding a secret: his family had entered the country illegally, meaning his lifelong dream of competing in the Olympics was in crisis. Competing internationally was impossible – something he admits he still cries about now.

Realising his potential

At his junior high school, Frimpong was recruited in track and field in 2001 and was coached by Surinamese Olympian Sammy Monsels. Akwasi went to the Dutch Junior Indoor Championships within two months, missing out on the 60m final by 0.01 seconds. That summer, he missed out on the 100m final, by the same agonisingly slim margin.

“I asked my coach what I needed to do to become a gold medallist. He spoke to me about self-discipline and it all started from there,” said Frimpong.

In 2003, he became the Dutch national junior 200m champion at the age of 17.

“Within 18 months, not only was I the best in my city, but I was the best in my country and won my first gold medal,” he says. “From then on, I knew anything is possible as long as you believe in yourself and you want it bad enough.”

Olympic dreams in tatters?

Unable to compete internationally, Akwasi told his coaches he had lost his passport and reluctantly turned down offers to compete for the Netherlands.

However, after confiding in his coaches, he was given a place at Amsterdam’s highly regarded Johan Cruyff College in 2004.

Frimpong studied public relations, marketing and communications – and went on to become International Student of the Year.

However, his illegal status meant he couldn’t travel to Barcelona to receive the award from the football legend, so Cruyff flew to Amsterdam to present the honour.

Switching things up

After a long struggle, Frimpong was eventually granted official residency in the Netherlands in 2008, meaning he could concentrate on training to qualify for the Dutch athletics team for the London 2012 Olympics. But just as quickly as his hopes were ignited, they were shattered all over again when he suffered a devastating Achilles injury.

Refusing to let the news crush his dreams, Frimpong toyed over his future for six months before deciding to trade the athletics track for the ice, securing a spot on the Dutch bobsleigh team for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

He says: “After missing out on London 2012, I was approached by the Dutch bobsleigh coach Nicola Minichiello about joining the team. I had my doubts, but then I remembered Cool Runnings and thought to myself, ‘If Jamaicans can do it, so can I!'”

But more challenges were on the horizon after Frimpong was dealt another blow when he failed to make the cut. He decided to sell his car and sell vacuums door-to-door near his training base in Utah.

The road to Pyeongchang

Frimpong’s bobsleigh coach told him not to give up and try a different sport – skeleton.

“I didn’t think I really wanted to do it,” he says. “A third sport trying out again, I was afraid of getting disappointed again. But my wife is the one that told me, ‘Hey, I don’t want you to be 99 years old and still be whining about your Olympic dream, so let’s go for it’.”

So Frimpong took part in a skeleton trial in Utah and immediately fell in love with the sport.

Mastering the sport usually takes four to six years, but Frimpong did it in less than two. By the end of 2016, he had reached 95th in the world rankings.

But his Olympic dream would only become a reality once he made it into the top 60, so he completed five races on three tracks around the world and successfully confirmed his qualification on 15 January 2018 – only two years after first racing.

Frimpong has now won eight gold, four silver and four bronze medals at local and international events.

The rabbit theory

Frimpong should be quite easy to spot on the ice, given his unconventional choice of headgear – a helmet featuring an image of a rabbit escaping from a lion’s mouth – something he attributes to his former sprint coach. The analogy is based on the ‘Rabbit Theory’, in which a rabbit is in a cage surrounded by lions.

“When the cage goes up, the rabbit has to run away from the lions otherwise it will get eaten,” explains Frimpong. “My coach referred to the lions as negative people, the bad people, the Dutch immigration; all the bad things that were going on in my life – those were the lions and I was not able to escape from them.

“So going to Pyeongchang after 15 years, I’ve worked really hard to eventually become the rabbit my coach always wanted me to be. So you see on my helmet a rabbit escape out of a lion’s mouth.”

Regardless of how he does in South Korea, his beloved fans in his native Ghana will always regard him as a hero. Or, as the locals say, “Ghana in 60 seconds”.