Cameroonian soldiers are using “extreme physical violence” to force tens of thousands of refugees fleeing the Boko Haram insurgency to return to northeastern Nigeria, Human Rights Watch has warned.

In a report released today, the rights group said Cameroon’s security forces have used torture and assault to drive at least 100,000 people back across the border since 2015, even though the government has signed an agreement with the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, to ensure returns are voluntary and only “when conditions were conducive”.

Many returnees have wound up in camps for displaced people in Nigeria’s Borno State that lack adequate food and services. They are unable to return to their villages due to the continued insecurity in the countryside, and the camps themselves are not always safe.

Cameroon is refusing to register tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers as refugees who are stuck in the border areas, HRW said. It fears infiltration by Boko Haram, who have mounted scores of attacks since 2014 in the country’s Far North Region – typically suicide bombings.

Cameroon’s zero-tolerance policy means more than 4,400 Nigerians were deported between January and mid-August this year and in the process people have been “tortured, assaulted, and sexually exploited”, said the rights group.

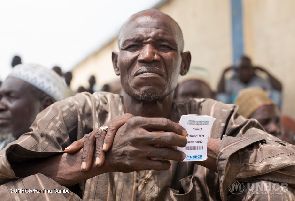

The report interviewed a refugee who was deported from the border town of Mora in March. He told HRW that he was one of 40 Nigerians rounded up by Cameroonian soldiers and forced onto a bus.

“They beat some of the men so badly, they were heavily bleeding,” he said. “When we got to the Nigerian border they shouted: ‘Go and die in Nigeria.’”

Cameroon “has correctly committed itself to protecting the lucky Nigerians who made it to the country’s only refugee camp,” said Gerry Simpson, HRW associate refugee director.

“But in the meantime, local authorities and the military are denying tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers protection who risk forced return to the carnage in northeast Nigeria,” he told IRIN.

Simpson said that Cameroon’s deportation of 100,000 Nigerians over the past two years “puts it on a black list of a handful of other countries committing unconscionable mass refoulement”.

UNHCR has also criticised Cameroon over the deportations, while urging Nigeria’s neighbours to continue keeping their borders open to allow refugees in.

Cameroonian Communications Minister Issa Tchiroma has, however, denied the accusations of forced returns. “This repatriation has taken place willingly,” he told the BBC in March.

“Abusive restrictions”

But the 70,000 Nigerians who have made it to Cameroon’s official Maroua refugee camp are only marginally better off than those playing cat-and-mouse with the authorities in the border regions.

The refugees have only limited access to healthcare, food, and water and are placed under “a strict encampment policy”, including what HRW called “abusive restrictions” on their movement.

In order to be recognised as refugees and receive aid, all asylum seekers are required to live in Maroua, built in 2013.

But asylum seekers told HRW how thousands of refugees left the camp in April and May this year in protest at the food shortages. The report said the World Food Programme had to cut rations in January by 25 percent due to a lack of funding.

Since the Boko Haram insurgency began in 2009, more than 20,000 people have been killed in Nigeria, with almost 1.9 million internally displaced. A further 200,000 have fled the country, sheltering in Cameroon, Chad, and Niger.

In Nigeria’s northeast, more than 7 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance and a further 5.2 million are food insecure. The potential existence of pockets of famine has been a real concern in a country where the humanitarian response is overstretched.

Nigeria has repeatedly claimed to have defeated the eight-year-old insurgency. But Amnesty International said in a report earlier this month that attacks on civilians by Boko Haram in Cameroon and Nigeria have doubled to 381 since April.

More suffering

There are security and humanitarian implications for refugees being forcibly returned to what is still an active war zone, said Cheta Nwanze, head of research at the Lagos-based geopolitical research firm SBM Intelligence.

“Entire villages in some districts have been laid [to] waste and are mostly uninhabited and uninhabitable,” he told IRIN.

“Critical infrastructure, such as roads and schools have been degraded by the effects of war, and the entire northeast region, one of Nigeria’s prominent agricultural producing areas, has had an underwhelming farming season for the sixth successive year.”

Nwanze added: “The refugee camps in the region are mostly overcrowded, understaffed, under-resourced, insanitary, and the federal and state officials in many cases have routinely creamed off critical humanitarian supplies meant for people in desperate need.”

In April and May, HRW says at least 13,000 refugees returned from Minawao to a displacement camp in Banki, just across the border in Nigeria. It was attacked by Boko Haram and at least 18 of those killed were from Cameroon.

Disconcertingly, HRW said on one occasion in late June 2017, the Nigerian authorities responded to Cameroonian pressure by sending military vehicles over the border to help Cameroon deport almost 1,000 asylum seekers.

This, the rights group, said makes Nigeria complicit in the unlawful forced return of its own citizens.

But Nigeria is trying to manage a difficult relationship with its eastern neighbour, said Nwanze. Cameroon is part of a regional military alliance that includes Chad and Niger and is aimed at Boko Haram.

“If the Nigerian side declines to cooperate on joint humanitarian and security concerns, a simmering but low-level situation could very well lead to a wider security contagion in the region,” said the security analyst.